Celebrating Dr. Sam Shemie, a world leader in organ donation

This Canadian physician’s passion to improve organ donation practices began with one of his own patients

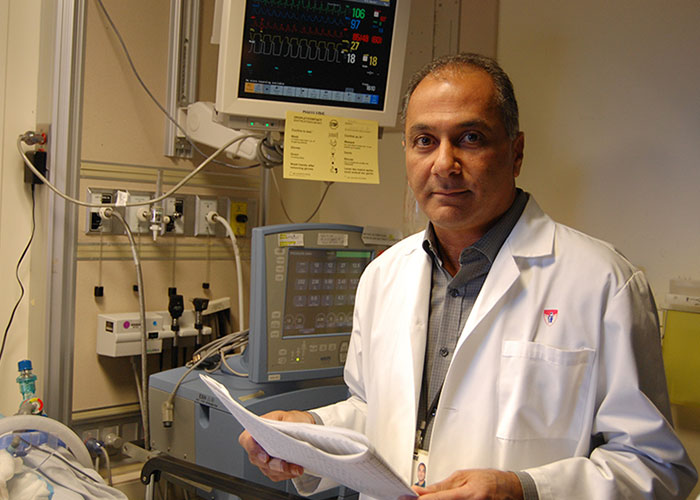

Dr. Sam Shemie’s drive to transform organ donation in Canada was sparked by a baby who needed a new heart.

Robbie Thompson was just six months old when he was admitted to Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) with end-stage heart failure. He was transported from Courtenay, B.C., and was in and out of intensive care for months afterward. Family life was upended as his parents paused work and left home to care for him in a faraway city.

As Robbie’s intensive care doctor, Dr. Shemie was at the centre of the story. Yet what struck him was how little control he had over the outcome for this family. A lifesaving heart transplant could only happen if someone else in Canada experienced tragedy, and if — once hope was lost — that other medical team helped make donation possible.

“Watching their journey in the ICU [intensive care unit], I realized that if we’re going to do this and keep this kid alive for a transplant, then I have to rely on all these other hospitals to do their job around donation,” says Dr. Shemie, who is now a medical advisor for Canadian Blood Services. “If they’re not doing their job, this kid is going to die, and we’ve wasted time, money, energy, and created trauma for the family.”

Fortunately, Robbie was able to receive a new heart at the age of 18 months, followed by a second transplant a few years later. He grew up to be an organ donation advocate, competing in athletic events for transplant recipients in Canada and abroad.

As for Dr. Shemie, he’s worked tirelessly for more than two decades to increase organ donation rates to honour the wishes of families on behalf of dying patients and to serve the needs of those waiting for transplant. He’s done it through efforts to change hospital culture, support the creation of a national system for organ donation, and shape understanding of death itself.

‘To advance organ donation, you need a team of people’

For physicians in intensive care units, the mission is clear: save lives and relieve suffering. So perhaps it’s not a surprise that historically, many have seen it as a betrayal of the patient to even consider organ donation in the course of their duties.

But Dr. Shemie, who is now a medical advisor with Canadian Blood Services, saw a need for medical professionals to better navigate that tension. After all, over the course of their careers, he knew these physicians would also treat patients who needed organs, not just those with the potential to become donors after death. If organ donation rates could be increased without ever compromising efforts of lifesaving care, they would save more lives overall.

So, Dr. Shemie and some of his like-minded colleagues began publishing papers describing the challenges around organ donation that they had experienced in the ICU, with ideas for how to improve the system.

“We published our results, and said that in order to advance organ donation, you need a team of people,” Dr. Shemie says. “You need ICU doctors, nurses, social workers, donor coordinators, and it needs to be 24/7. You need to fix the problems of people not understanding brain death. And it has to been driven by the highest standard of medical, ethical and legal practice.”

In large part because of Dr. Shemie’s efforts, organ donation has gone from being seen as a conflict of interest, to an area of specialization for more than 150 donation-focused ICU doctors across the country. Either directly or indirectly, Dr. Shemie has mentored virtually every physician in Canada with involvement in organ donation.

“Dr. Shemie was instrumental in my development as an expert and advocate for donation in Canada,” says Dr. Sonny Dhanani, chief of critical care at CHEO, the children’s hospital in Ottawa, Ont. “He fostered curiosity and compassion from early in my training as a critical care physician and has unselfishly given me opportunities to develop, grow, and shine.”

Leading efforts to better define death itself

Beyond cultivating the next generation of donation and transplant specialists, Dr. Shemie is also deeply respected for instigating big picture change.

“Sam taught me that as important as it is to be a great clinician, if you really want to make a difference for the population, you need to make an impact on systems,” Dr. Matthew Weiss, medical director of organ donation at Transplant Québec, says. “Sam has taught and continues to teach me to bring the same level of rigour to those administrative problems as I would at the bedside.”

An example is Dr. Shemie’s national role with the Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation. The council was created in 2001 by the federal government to help federal, provincial and territorial governments coordinate better on organ donation. One of its priorities was to create standards for organ donation which could be applied across the country.

In 2005, in his role with the council, Dr. Shemie led a forum to develop recommendations for donation after cardiocirculatory death in Canada — in other words, donation after the withdrawal of life support, and after several additional minutes with no heartbeat. Previously, donation was only allowed if there was no brain activity. This greatly increased the chances of organs being made available for transplant.

Dr. Shemie continued work in this important area, in partnership with Canadian Blood Services and other leading health organizations, to create a 2023 clinical guideline for defining and determining death.

Making Canada ‘an ethical leader in donation and transplantation’

With Dr. Shemie, the council also helped pave the way for Canadian Blood Services’ efforts to create the Canadian Transplant Registry. This software allows for precise and fast matching of organs, wherever donors and potential recipients are located in Canada.

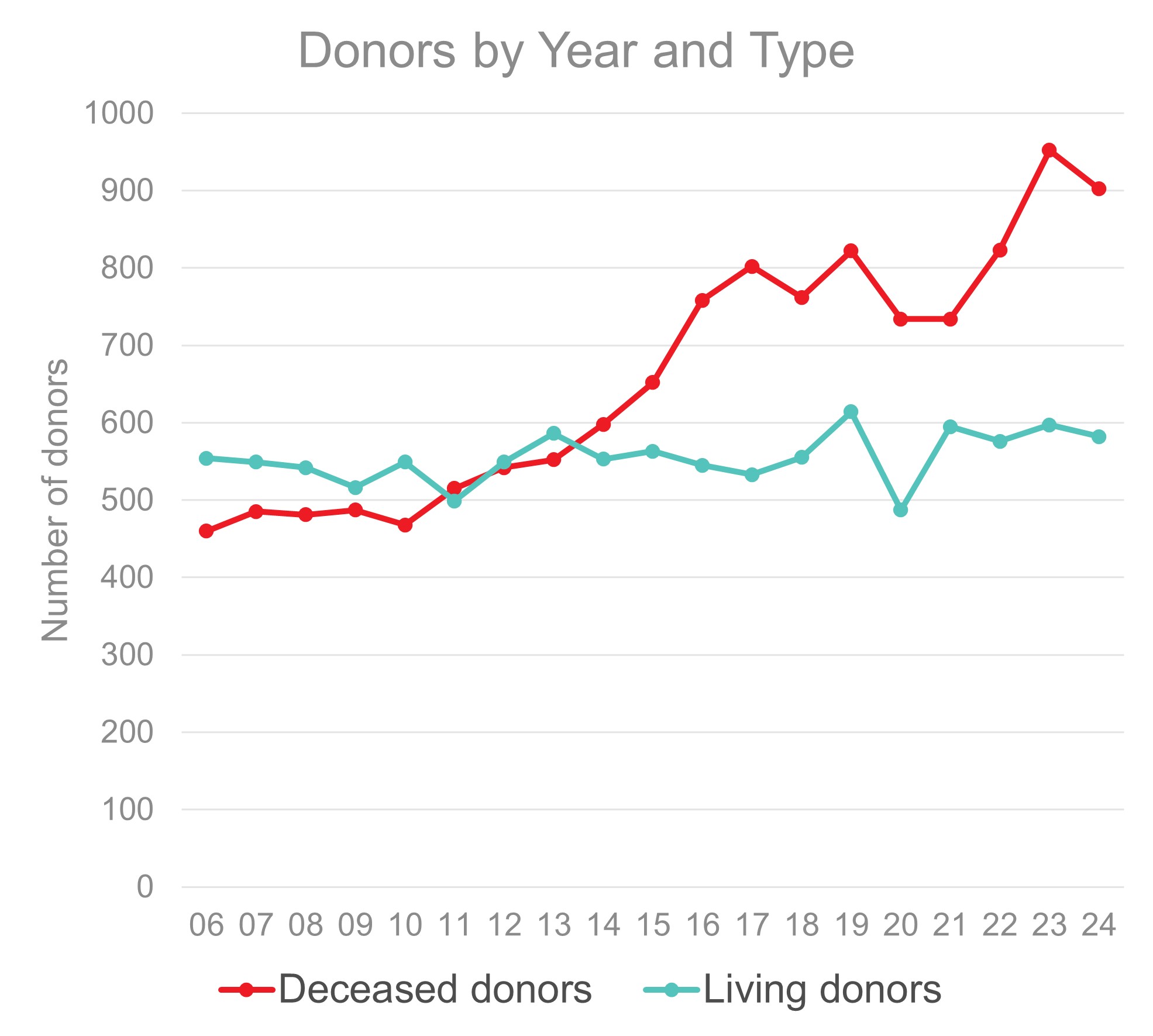

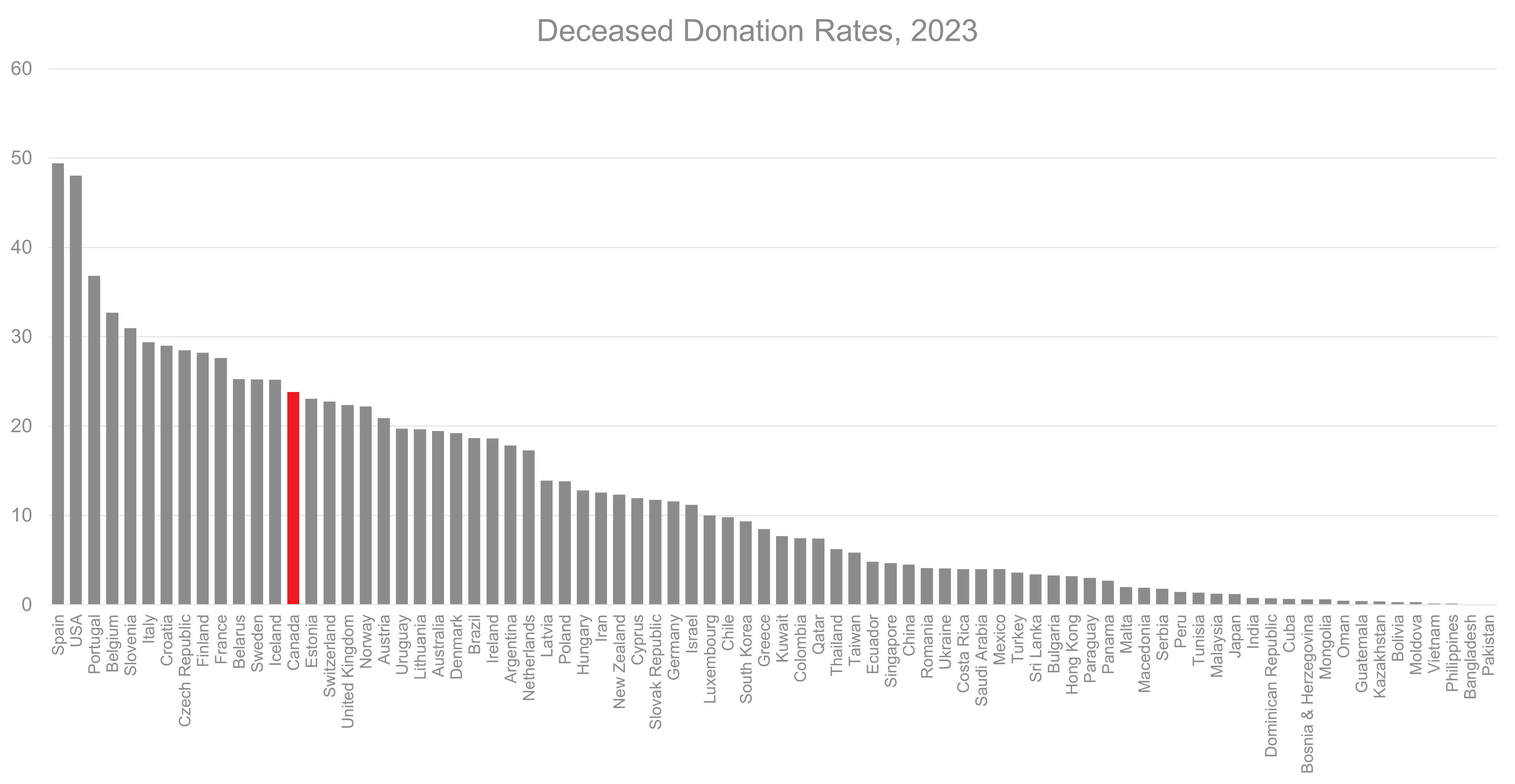

In fact, over the past two decades, the deceased donation rate has increased by more than 60 per cent thanks to concerted efforts to improve the performance of the system.

“We went from a stagnant rate of 10 donations per million population and at the bottom of the list internationally and always having to ask other countries advice on how to do things,” Dr. Shemie says, “to now being seen as an ethical leader in donation and transplantation, producing guidelines and research, and our donation rate is in the 20s [per million population] which is the top third in the world.”

“In my mind, if you remove Sam Shemie from this work and the same 25 or 30 years would have passed, the entire landscape would not look like it does now. It’s that profound,” says Dr. Samara Zavalkoff, an intensive care unit physician at the Montreal Children's Hospital. “Without Sam we would still be where we were 25 years ago.”

In recognition of his remarkable contributions to organ donation and transplantation in Canada, Dr. Shemie has been appointed a Member of the Order of Canada and has received the King Charles III Coronation Medal. In Quebec, where he now works as medical director of the pediatric intensive care unit at Montreal Children's Hospital, Transplant Quebec also awarded Dr. Shemie with its highest award, the Grand Prix, in 2024.

“The great thing about Canada is that we are a collaborative country. You can’t force things top down. You have to do things collectively and that takes leadership,” Dr. Shemie says. “I've been lucky to be able to lead efforts in the area of organ donation, and have other capable leaders continue those efforts.”